Breguet's aesthetic codes: uniqueness and excellence

21 December 2023What makes a Breguet unmistakable? What distinguishes it from any other watch? Quality, certainly. Mechanical excellence, certainly, but there is something more complex that makes a Breguet a Breguet. Something that, in watchmaking, is often more important than precision, technical mastery, research and development: the aesthetic codes. What, then, is a code?

The Treccani encyclopaedia, among its various definitions of ‘code’, provides this one: ‘In a more abstract sense, in contemporary linguistic and literary terminology, any organic system of symbols and references enabling the transmission and comprehension of a message, the meaning of which can only be understood if speaker and listener (or writer and reader) use the same code’.

A definition that fits in well with watchmaking codes, a knowledge common to the habitués of the sector, which enables them to identify precisely the message it conveys. If we talk about crown-protecting bridges, or floating lugs, or grand tapisserie, anyone who loves watchmaking knows exactly what we are referring to. A code very often identifies a brand, and a brand is such because it has one or more codes that it carries from birth.

BECAUSE BREGUET IS BREGUET

Breguet is one of the brands that presents plenty of its own – and only its own – stylistic codes. Codes that other brands have not infrequently borrowed, but which are firmly rooted in its history and remain unmistakable. If they assume a key importance in watchmaking, for Breguet they represent the very essence of the brand, what gives it its unique and inimitable character.

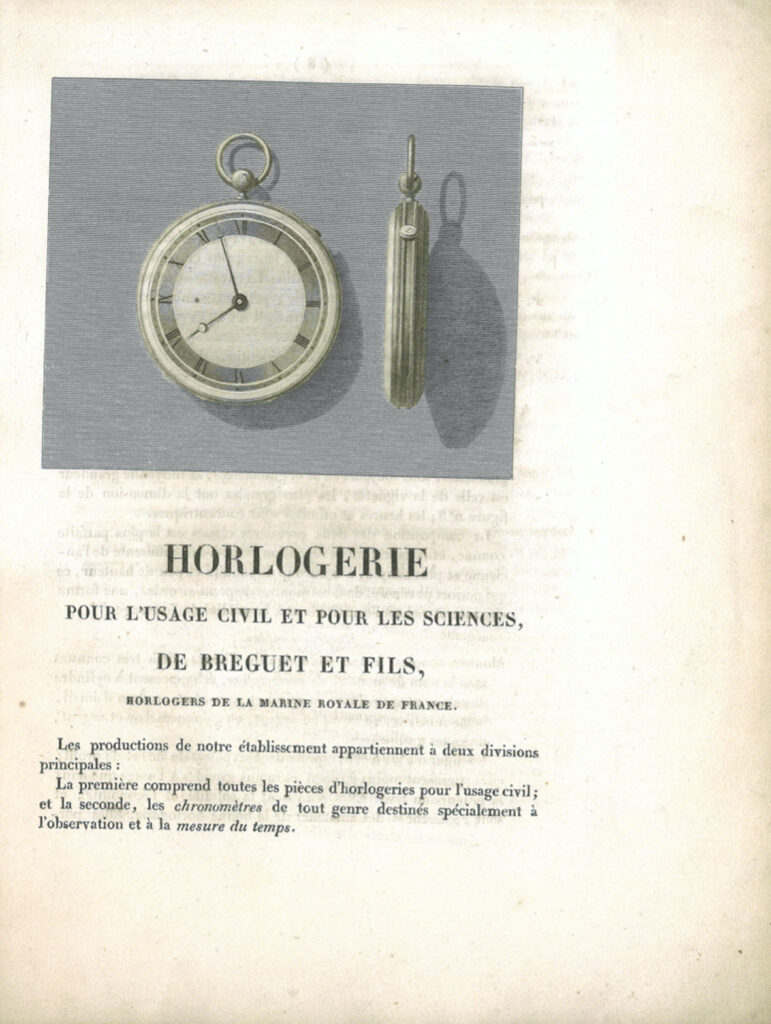

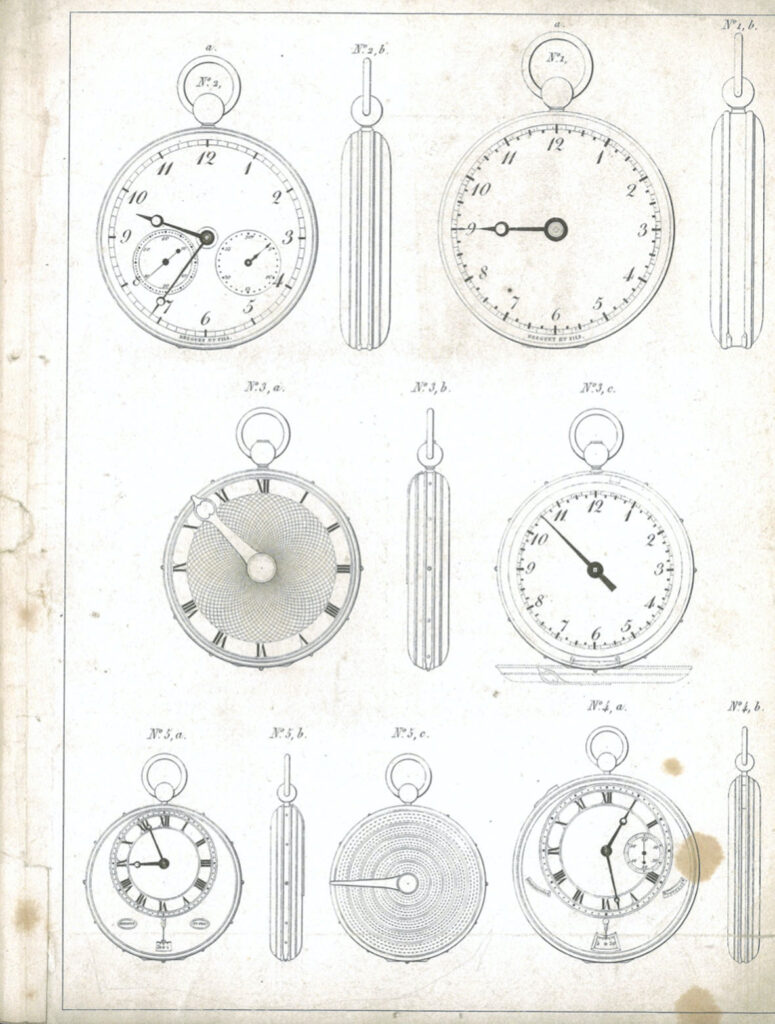

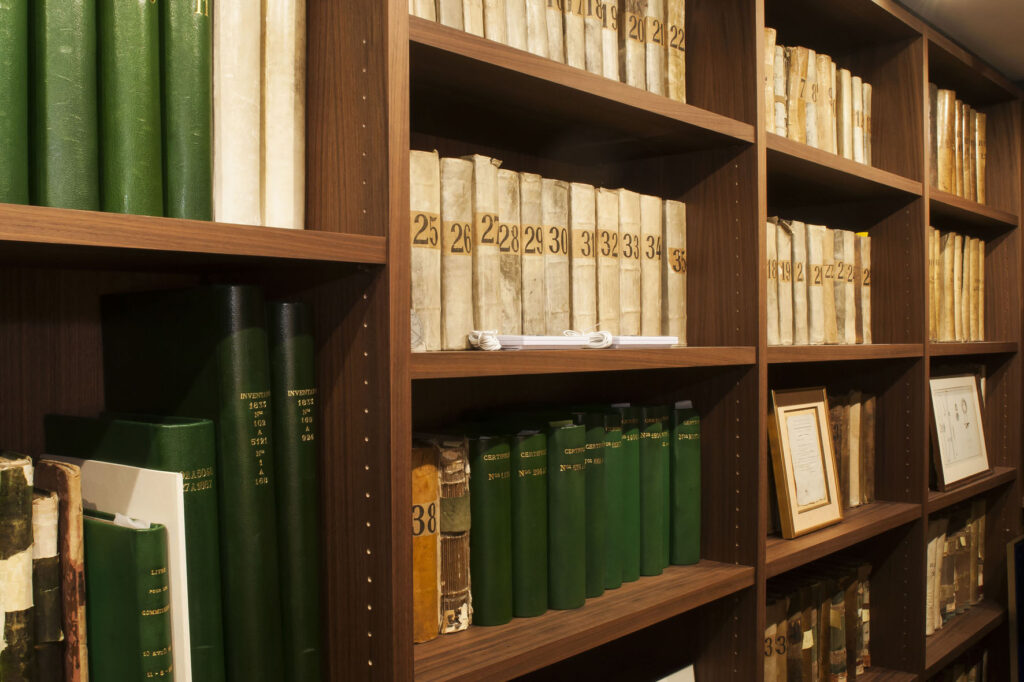

Unlike other brands characterised by only one or two specific aspects, Breguet’s stylistic codes are numerous. They are the fruit of a way of conceiving the watch and watchmaking that goes right back to Abraham-Louis Breguet, as evidenced by the first known watch catalogue dating from 1822. It was French and its title roughly translates as ‘Clocks for civil use, portable chronometers, marine and astronomical clocks, and other observation instruments’.

The introduction to the Breguet models of the time is enlightening to understand where the vision of watchmaking at the heart of thebrand’s style and design comes from: ‘The elegance of the forms, the choice and proportions of the case fillets or grooves, the effect created by the rounding of the case edges and the semi-flat crystal, the finesse of the dials’ guillochage and the lightness of the hands, the contrast between the opacity and the metallic brilliance that distinguish the models could not be rendered by the engraving of the line and the geometric design, which were always unflattering’.

In short, at a time when photography did not yet exist, a fine design was unable to produce watches whose aesthetics weren’t far from perfection. The characteristics of these aesthetics are still found today, some of which are mentioned in that very catalogue written 200 years ago. Let us look at them.

THE ‘À POMME ÉVIDÉE’ HANDS

This is one of the most striking features associated with Breguet watchmaking – partly because the hands take centre stage on the dial, partly because they are a mobile, living element. They were born around 1783, following Abraham-Louis Breguet’s desire to simplify the design of the hands of thetime, which were often short, wide, and highly decorated. This design made the entire watch heavy and made it difficult to read the dial.

Breguet himself had always used English gold hands which, around 1783, gave way to new ones in gold or blued steel. They were described as ‘à pomme évidée’ (literally ‘emptied apple’), and the principle guiding their design was to eccentrically empty the tips. It was a small, big revolution that immediately led to that type of design being identified as ‘Breguet hands’.

In a way, Abraham-Louis Breguet’s choice to offer thin blued steel or gold hands, with a delicate off-centred sphere hollowed towards the end, represented a complete overturn of conventions. A choice so deliberate and irrevocable that, from the moment this design was created, neither Breguet himself nor his son ever deviated from it again.

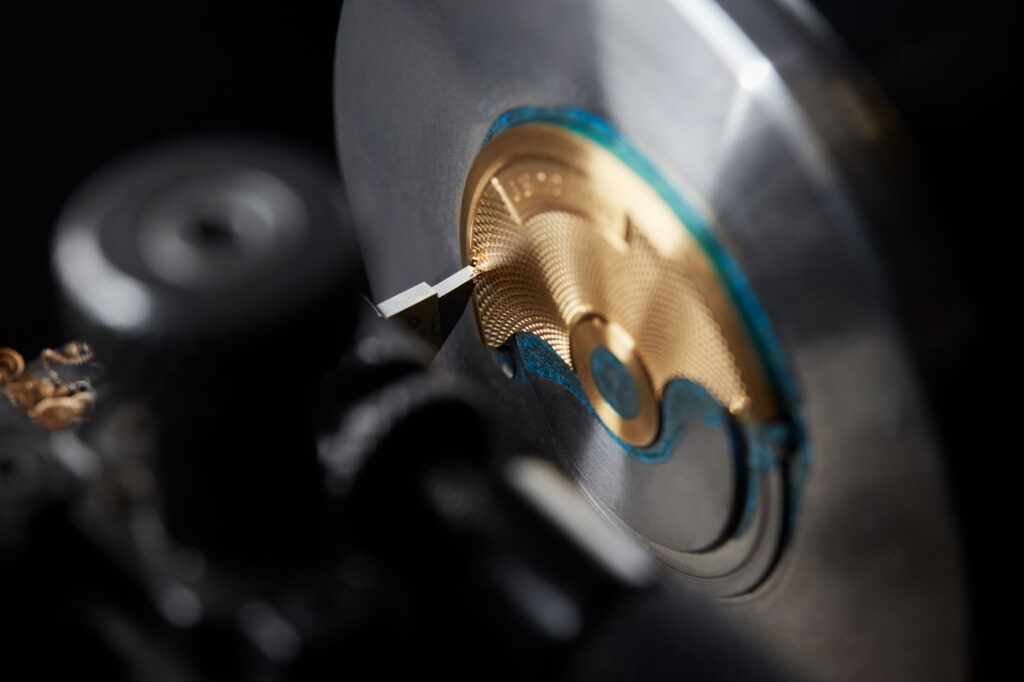

THE GUILLOCHÉ PROCESSING

It was certainly not Abraham-Louis Breguet who invented the guillochage technique. It was already very much in vogue during his time, used mainly in the artisan world to decorate ornamental objects of a certain value. What was still missing was the stroke of genius, the classic situation so obvious that no one had yet thought of it: why not apply guilloché on watch dials to embellishthem? Said, done.

This decoration became so typical of Breguet dials that it found its way into the catalogues of the time, where they pointed out that the technique demanded total delicacy from the craftsman engraver in its execution, precisely because it was applied to objects as small and fragile as dials made of gold or silver.

With the guilloché decoration, Breguet achieved two objectives. On the one hand, he lightened the visual impact of the dials, making them suitable for his new hands with their fine and sober design, which harmonised optimally with the overall structure of the watch. On the other, he improved time legibility by using different decorative motifs to differentiate the zones or sectors of the dial itself, on which to place the different indications.

Above all, this last idea proved so ingenious that it is still one of the hallmarks of Breguet watches today, especially in the most elegant collections such as the Classique. It is proof of the modernity of a man who, almost 250 years ago, had already shaped the future of watchmaking, both technically and aesthetically.

BREGUET NUMERALS AND DIAL DECORATION

It is precisely on the dials that we find some of Breguet’s other stylistic features. Although the guilloché motif was one of the brand’s ‘fingerprints’, it is true that not all dials had this type of decoration. In fact, those of watches without complications were generally in white enamel, smooth and plain – although the enamel work itself was anything but banal and required a high level of craftsmanship.

Since, as we have seen, the delicate guilloché engraving had not only an ornamental function for the dial but also a practical one for delimiting the areas reserved for the complications, enamel dials were not usually used on watches with complex functions that went beyond the simple and practical display of time. For timepieces with enamel dials, however, another distinctive stylistic code of the brand was reserved: the so-called Breguet numerals.

On models with guilloché dials, Abraham-Louis Breguet preferred to use Roman numerals for the hourmarkers, classic and timeless. For the models with enamel dials he reserved Arabic numerals, but in a new, light typographic style that combined elegance, legibility, aesthetic knowledge and savoir-faire.

Thanks to a slightly inclined typeface, which was neither cursive nor square, but subtle, whimsical and at the same time bold, the numerals on the dial were exceptionally legible without being cumbersome. A typographic style that stood the test of time and is universally known in modern watchmaking as ‘Breguet numerals’. Another of those codes that are found here, and only here.

THE COIN EDGE CASE

Since Abraham-Louis Breguet conceived the watch as an organic whole, the case was also of fundamental importance to him in conveying the brand’s aesthetic codes. The most obvious, which has come down to us unaltered, is the grooves decorating the side of the case, almost like the knurling of a coin. In the past, this technique was applied on pocket watches, along with decorative motifs on the front and back covers.

These decorations increased the aesthetic preciousness of the watches, but they also had a practical function. They allowed the precious timepieces to be gripped securely, reducing the risk of them slipping out of their owner’s hands and falling on the ground, with catastrophic consequences. Guilloché motifs on pocket watches’ lids had the same ‘increased grip’ function, and would prevent fingers from leaving unsightly marks on the timepiece.

Nowadays, as wristwatches have largely supplanted pocket watches, it may seem less important that the case’s finishing prevents the risk of the watch slipping through your fingers. It is true, however, that even today watches come off the wrist to be stored or, in the case of manual calibres, wound. Hence, the presence of grooves on the case in modern collections fulfils the same function, while also adding a refined and elegant touch to the piece.

Speaking of cases, it is worth noting another characteristic typical of Breguet watches. It is not a true stylistic code, but nevertheless it reflects the aesthetic vision that master Abraham-Louis had when he designed a model. On his timepieces, in fact, Breguet always sought to make the case’s and dial’s proportions well balanced; in this way he gave the dial a maximum diameter and the bezel a minimum thickness. A combination that gave more space to the indications, improving their legibility, and lightened the overall appearance of the watches. The best practical translation of this theory today is the Classique collection.

THE DISPLAY OF INFORMATION

Finally, returning to the dial, we find another innovation introduced by Abraham-Louis Breguet that shows how far ahead of his time he was and that has also become, in this brand more than in others, a true stylistic code: the use of windows for thedifferent indications. A solution that may seem obvious and banal to us, 21st-century people, but which in the master’s time was not at all.

The decision to use windows on the dial was always in response to the need for lightness that led to the proportions of the case, the use of guilloché, and the ‘à pomme évidée’ hands. In essence, Breguet did not want to overload the dial with an exaggerated number of hands. He therefore decided to adopt a solution that was not new, but which until then had only been used on a larger scale on large table or floor clocks, and reserved mainly for moon phases and astronomical indications.

Abraham-Louis Breguet had the intuition to miniaturise this type of indications and apply them to pocket watches. What’s more, he did not limit himself to using the windows for astronomical information, but used them to indicate the day of the month, the month itself and the day of the week. This miniaturisation work was not trivial, because it required extremely high craftsmanship qualities and was carried out on dials made of precious materials: making a mistake meant throwing everything away, with heavy economic losses.

In addition to the windows, another typical feature of Breguet’s watch dials is the marked penchant for the off-centre position ofthe hour circle, which comes from the master’s own vision. Indeed, from 1812 onwards, this tendency can be found on most of his most famous creations, which would later be adopted with even greater vigour by his son.

The decentralisation of the indications on the dial is not always the same. It may tend towards

the bottom, the top, or one of the two sides. In all cases, it enables Breguet to position the watch’s various functions and indications in new ways, while always ensuring that the timepiece and the dial do not lose their visual and aesthetic harmony. An essential point in Abraham-Louis Breguet’s vision of watchmaking, also embodied in some of today’s collections.

BREGUET’S LEGACY IN TODAY’S COLLECTIONS

To the initial question ‘What makes a Breguet unmistakable?’, we have tried to answer by exploring the brand’s stylistic codes, without neglecting to mention their importance in the world of watchmaking. Because even today, they make each watch recognisable, speaking a universal and common language that enthusiasts know and with which they identify.

In the 21st century, this language of Breguet is widely present in all its collections, from the most elegant to the most sporty, although the concept of ‘sporty’ for the brand is rather original and nuanced. However, there are two lines in which, in our opinion, this 18th century heritage is most present: the Tradition and Classique collections.

Of the former, we recall pieces such as the Tradition 7047, the Quantième Rétrograde 7597, or the Automatique Seconde Rétrograde 7097 which we have already discussed on Watch Insanity. These are all watches in which the harmony of the dials, the display of information, the excellence of the mechanics and the meticulous workmanship of the cases would make Monsieur Breguet proud if he were alive today.

About the Classique it isworth mentioning masterpieces such as the Tourbillon Extra-Plat Anniversaire 5365, the Double Tourbillon 5345 Quai de l’Horloge, and the Tourbillon Extra-Plat Squelette 5395. Or two timepieces that are the epitome of elegance and simplicity, capable of concealing some of the most sublime mechanics: the Tourbillon Extra-Plat 5367 and the 5177 Grand Feu.

We have limited ourselves to a small and by no means exhaustive selection of what the brand is still capable of today, rooted in a unique history and tradition. If Abraham-Louis Breguet is rightlyconsidered the father of modern watchmaking, this title does not derive from his unrivalled technical expertise alone. He deserves it because, as written above, he was a man capable of being ahead of his time, of looking beyond the present to imagine and create the mechanics of tomorrow. Mechanics, but also aesthetics, with codes that have marked not only his timepieces, but history. We all know how to distinguish the paintings of Leonardo, Caravaggio, Monet or Van Gogh by their unique and exclusive codes. From canvas to wrist: the same applies to Breguet.

By Davide Passoni